If you’ve stumbled across this piece hoping for a plaintive call to keep football the same, or to return it to the “glory days” (whatever they are), you’ve clicked on the wrong article. Our thesis is instead: change is generally good where it is reasoned and researched, while unnecessary or rash change is generally bad.

The game of Australian Football is just over 150 years old, in a codified form. Like a lot of good things in Australian society, the first rules were thrashed out in an afternoon at a pub after intense discussion.

The seven drafters of the ten original rules would barely be able to recognise the game as they drafted; which is likely a very good thing. In the beginning, players couldn’t pick the ball up off the ground, the handpass and bounce (both starting and running) had yet to be thought of, a level of casual “scrimmage” violence was permitted which would be outrageous today, and there were no umpires, amongst lists of other things.

According to a list provided by occasional HPN contributor/Footballistics co-author/general friend of the program Ryan Buckland, there have been 173 changes to the rules since the first 10 were adopted in 1858, a rate of change that’s accelerated in recent decades.

It is clear that the historical process of rule change has been one of largely trial-and-error; think the two months in 1930 where dropping the ball in tackles was allowed, before outrage caused it to be banned again. Or the nine years where the flick pass was abolished, before returning for three decades before being removed again.

Some was a matter of interleague rivalry and interstate politics, with the two handed throw-pass being legal in the VFA in the 1930s and 1940s. This was also being proposed as a national rule change by Tasmania in 1938, without seconding support.

Readers interested in the story of this development and change of rules and tactics over the whole history of the game would be well advised to pick up a copy of Time and Space by James Coventry.

Measuring play back then is tough, due to the lack of ways to do so. Aesthetic views and raw scores were about the only two measures on the table; it was what we would these days call an information poor environment. As a recent twitter poll from Insight Lane shows, what most people think of a good game of football differs greatly from person to person; as it would have done back then.

For an upcoming fact-based blog post, I'd like the public's opinion on which factor is the biggest contributor on the 'quality' of an AFL game.

Which factor is the most important in a game's standard to you as a consumer? Please RT.

Expanded definitions in the following tweet:

— InsightLane (@insightlane) July 19, 2018

The creation and reversal of various rules over the years indicates that a gut-feel based approach to changing the framework of the game is at best prone to errors and reversals, and can sometimes be outright terrible. In an IT sense it would be called “testing in production”, which will get you fired from a fair number of gigs in that industry.

But there is a better way than relying on the gut

The historical gut based approach of rule changes in Australian Rules wasn’t uncommon across the world of sport in bygone eras, but is less frequent today.

Perhaps the most prominent example of a major rule change being successfully implemented by intuitive thinking, without evidence, driven by strong need, is the creation of the forward pass (and removal of mass formation plays like the running wedge, amongst other changes) in American Football. This occurred by a committee at the suggestion of President Teddy Roosevelt, and was designed to reduce deaths in the young code. In time, this had the effect of changing the entire code from its heavily rugby influenced base to the wide open game we see today. But that transformation wasn’t the intention of a rule change aimed mostly at helping players not die; it was merely the eventual outcome.

These days three of the four major US sports tend to implement most rule changes in a similar manner to each other – they test changes in the minor leagues, before changing the major code.

Testing in a practice league is good! It is probably best practice!

The NBA G-League (formerly the D-League) has run with a wide range of experimental rules over the years, from different shot clock and timeout laws, to the use of four referees, to the length of overtimes, and other rules. Some of these changes have been successful in their intended goals and implemented in the NBA, others have been consigned to the dustbin of history. Which is exactly how testing should work.

There are also other examples, from free baserunners in extra innings of Minor League Baseball games, to stricter anti-fighting rules in the American Hockey League (the NHL feeder).

This is what we would call evidence-based decision making. These leagues assessed the actual, real world impact of these changes over a long period of time to ensure that the changes were effective, and there were no unintended impacts.

It is worth noting that the AFL trialled the use of four umpires in games mid-season in recent years, sometimes without any acknowledgement that they would do so prior to the year starting, or without any long term testing at lower levels.

The AFL already has experimental data to draw on

Australian football has begun experimenting in this way, demonstrating that it has some understanding of the concept of beta testing. Brief training runs are admittedly a pretty limited tool, given the lack competitiveness and sample size, but at least it’s a start, and there’s other examples.

The TAC Cup has several innovations particular to its status as a recruitment ground, such as anti-density zoning rules, and restrictions on tagging. Rule change here is geared towards allowing the most talented individuals to showcase talent and get drafted.

Anti-density rules, enforced mostly as a “philosophy” for coaches in what is a development league, penalised more by club punishments than on-field sanctions, were introduced in 2014, seemingly to the effect of a bit under one goal per team per game. That effect has dissipated in more recent years, however.

In the past two seasons scoring has dropped relative to the two years prior to the introduction of the rules. We’d also note that youth development league “enforced philosophies” may not directly translate to the more cynical and team-oriented professional environment.

There’s also a trickle of past and present natural experiments, such as the VFA formerly being 16-a-side competition, and the independent SANFL currently using a three-man bench, lower rotation cap, and a last-disposal out of bounds rule to eliminate the need for umpires to interpret intent.

The last disposal rule was introduced in the SANFL 2016, and gives a free kick to the opposition whenever any kick or handball goes out of bounds. That means spoils, fumbles and deflections are not penalised. Again, it appears as though there was about a one goal per team per game impact the year the rule was introduced, and again the impact seems to be later reduced or outweighed by other factors over time.

Regretfully the AFL has also chosen to experiment in a top level competitive league, the AFLW.

AFLW changes have included the replication of rules which have existing data available from other leagues, such as the SANFL’s last disposal rule, 16-a-side play like the former VFA, and centre bounce zones like the TAC Cup.

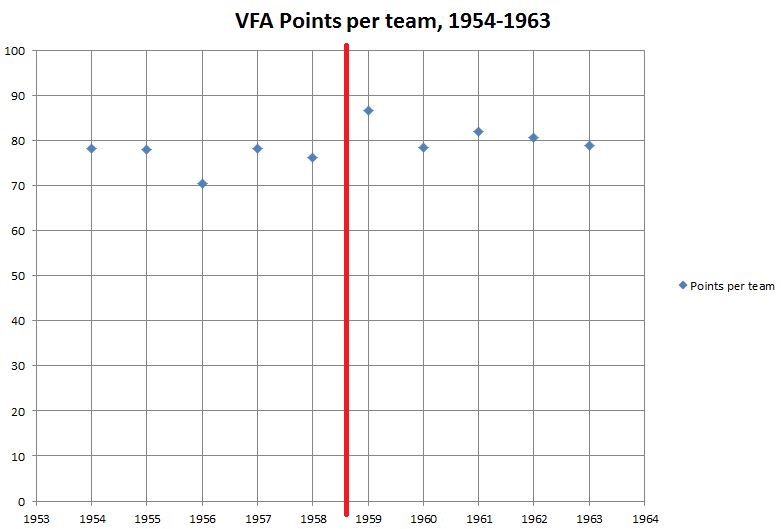

The AFLW has been 16-a-side since it began. As we indicated in a previous chat on rule changes, the VFA trial of 16-a-side had an immediate impact (like the other examples above) which dissipated over time.

This experimentalism is a little demeaning and disrespectful to the serious elite women’s league it is trying to build. It’s not a development league and it’s not a subordinate tier of footy.

Introducing a mid-season rule change in the introduction of starting zones was particularly egregious. The impact of the introduction these anti-density rules after Round 1 in 2018 was minimal at best. There was an increase of scoring of about one goal a game (surprise) before and after the implementation of the rule (or “non rule” as was insisted at the time). This boost to scoring, however, was less than the post-round 1 increase in 2017, which saw scores increase eight points after round 1.

Doing nothing, it seems, was more effective than introducing a mid-season rule change, admittedly across a small sample.

Not content with the backlash from mid-season changes to its lower profile women’s competition, which were at least applied on a competition-wide basis, the AFL today bizarrely floated the idea of trialling rule changes in-season, in specific selected games, in the national men’s competition. The justification for this is apparently that “some games don’t matter” due to clubs not being able to make finals. Which is crazy from every policy-making, commercial, competitive integrity, and public relations angle we can think of.

What’s strangest is that the AFL has plenty of sensible options to undertake a much better change process. The AFL directly controls at least two state leagues – the NEAFL and the VFL – in which it could tinker and experiment to its heart’s content. It may well soon control the state league in Tasmania as well. It could also even potentially work with the WAFL and SANFL to trial things, echoing the way the VFA used to look for changes as a point of difference to attract interest.

That’s potentially four different petrie dishes to try things. That allows a large sample size and even simultaneous comparisons alongside control groups at a semi-professional and reserve grade level.

At a basic process level, we just don’t understand why they would float something as prima facie stupid as mid-season, game specific, rule changes when the potential for actual serious evidence-gathering is right there within the league’s grasp.

Evidence based decision making should not be optional, and nor should be the want to accumulate extra evidence.

You left off the “QED” at the end.