When discussion of recent or future AFL expansion arises, it is often followed by claims from various pundits claim that the addition of extra teams impacts on the quality of football by spreading the talent base too thin. At the most basic level, this makes easy logical sense – akin to trying to make a batch of pizza sauce spread over one too many pizzas.

It won’t be a good pizza; and it won’t be good football.

For example, Garry Lyon argued against a Tasmanian team being added because he doesn’t “think the footy is at the standard across the board that it has been because of the dilution of the talent pool” and Nick Dal Santo agreed saying “I don’t think we can add another 45” players. Cameron Mooney argued in 2015 that 18 teams was too many and that “the longer we go with a diluted competition, the longer we will be hurting the product”. Wayne Schwass called for a return to 16 teams in 2018.

The consensus in all these takes is that football is worse, and it’s worse because there’s too little talent to go around, compared with the golden ideal of the past. But is talent like pizza sauce, or is there a bit more to the equation than a simple look shows?

What is “the past”?

The first thing to do is to determine what “the past” is. Initial research by HPN indicates that “the past” covers a very long time. Who knew!

So let’s narrow it down a little – at the start at least. Given they’re discussing current expansion teams and not the addition of the Adelaide Crows in 1991 and Fremantle in 1995, we can more or less assume that the “talent thin” crowd might be fans of the 16-team era of the AFL. This period lasted from the introduction of Fremantle in 1995 to the introduction of Gold Coast in 2011. If an initial baseline is required, the period just after the establishment and bedding down of the national competition makes sense.

So, is there any evidence or numbers to back up the claim that the talent pool is “diluted” in the contemporary era compared to the mid 1990s when the AFL first added a 16th team?

Australia’s population keeps growing

Here’s a pretty obvious observation – Australia’s population has significantly grown since 1995. In fact, outside of war, famine or massive disease outbreaks, Australia’s resident population has grown year-on-year since Federation. This is HPN pitching for a job as Captain Obvious.

Before you close your browser window, let’s break down the sample period a little more.

Australia’s population has grown about 42% since the 16-team era began, from about 18 million in 1995 to almost 26 million in 2020. In that time, the AFL has added two teams, representing a 12.5% increase in clubs and, due to slightly larger modern lists, a 19% increase in the player base.

On the face of it, that should be case closed. With more people in Australia per team than in the 1990s, our default position should be that the talent pool has expanded relative to the league size, not contracted. But there’s plenty of other variable factors and objections no doubt springing to the minds of readers, so let’s dig deeper.

There are more footballers, too

Could it be that there are less football players in Australia in spite of the larger population? One could imagine reasons to believe in a declining player base against rising population. Those could include expensive junior registration, video games, increasingly time-poor parents crushed by the demands of late capitalism, or the migration of many non-AFL fans to Australia from Great Britain and elsewhere.

However, it doesn’t seem to be the case that the number of Australian football players in the country has shrunk or remained stagnant compared to the 1990s.

Sources on player numbers can be found in population surveys, formerly done by the Australian Bureau of Statistics:

This source of historical participation data is the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ collections of adult and children’s participation of sport, which were collected intermittently with different survey methods from 1995 to 2014.

More recently, Sport Australia has collected participation data by contacting a private survey called Ausplay, but with voluntary response and a low response rate, their higher numbers (estimating roughly 585,000 Australian football participants in 2018) might not be comparable to the historical series. They do support the proposition that there’s not been a decline or stagnation in player numbers, however.

With the data available, despite the breaks in series, we can be pretty confident that the number of people playing Australian football has grown since the 1990s, if not in line with population, then somewhat close to that growth.

By the way, the growth specifically in young men’s participation has also matched these overall figures, going up by about 50% from 1996 to 2012, and being higher still in the recent AusPlay data.

There are also secondary factors around football’s popularity which have at least kept pace with population growth since the 1990s. There are community ground shortages in parts of the country, attendance per game and in the aggregate has increased. The TV deal is much bigger. These also point to a growing talent pool. Not only are there more people in Australia than 25 years ago, there are also more footballers.

New talent pools are being tapped

Raw population growth, it turns out, actually greatly underestimates the talent pool available for recruitment because the AFL has expanded its reach beyond the traditional centres of the sport, recruiting players today who simply would not have been available in the beginning of the 16-team era.

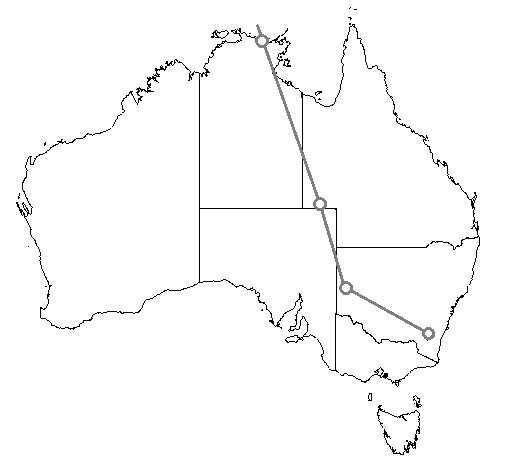

First, there’s the northern expansion of the AFL. Australian football is the dominant sport in roughly half of Australia, divided by what Ian Turner called the “Barassi Line” in 1978. His line looked like this, connecting Canberra, Broken Hill, Birdsville and Maningrida:

Traditionally, very few top level players have come from the north and east of this line. In this area covering over half the Australian population, the two rugby codes held sway along with soccer being more popular in New South Wales than the rest of the country. In the mid 1990s, there were only about 54 players on AFL lists from New South Wales, Queensland, and the ACT (which straddles the divide). Only 24 players came from genuinely monocultural rugby country (Queensland and the parts of NSW north of the divide).

The contemporary era has seen the higher northern profile of the AFL, locally situated professional teams, and focused development efforts greatly boost recruitment from non-traditional talent pools. On 2019 lists, there were roughly twice as many (about 105, up from 53) players in the AFL from NSW, Queensland and the ACT compared to 1996. The major gains were Queensland contributions doubling in number and recruitment from Sydney and coastal NSW increasing significantly.

Additionally, recruitment from overseas (principally Ireland) has stepped up a lot, further adding to the talent pool. In 1996 the only Irishman in the league was Jim Stynes and the Irish Experiment was faltering, with the number of Irish players even reaching zero in 1999. In 2019, there were 14 Ireland-born players. There is also Mason Cox as an example of recruitment from the vast American college talent pool, a source of tall players which will probably also expand over time. Not all overseas players have been success stories, but by the same token neither have been players from traditional recruiting pathways such as the Geelong Falcons.

Put it all together, and we can see that half of the growth in AFL player numbers from 1996 to the present day has come via new talent pools:

There were roughly 62 more players in the AFL from the five heartland states and territories in 2019 compared to 1996, and roughly 66 more players from outside those five states and territories. When we recall the population growth that’s occurred in that space of time, it’s clear that thanks to these developing pools, there’s actually a far lighter burden falling on Victoria, South Australia and Western Australia than there was in the 1990s era.

Fringe players are contributing more than they used to

It’s one thing to look at the big picture of how many players – in total – are in the broad talent pool. But perhaps more important is how many *good* players are in the talent pool.

Another way to measure the talent base is to look at how dominant the stars are in the league. If there is a weaker talent base, then reasonably we should think that there’s more list-cloggers getting undeserved games while not contributing much. We should expect to see goals, clearances, inside 50s, and other valuable contributions being more concentrated in the hands of fewer players. We should see the starts being especially dominant, during periods of weaker talent availability.

HPN’s Player Approximate Value (PAV) is a measure of player value designed to be consistent over a long period of time, letting us compare the period from 1988 to today using the same terms. Using the Gini Coefficient, a common measure of inequality, it is apparent that player value across the league has become more even over time. That is to say, a greater spread of players are providing value, the output is more evenly distributed across the league..

It’s the earlier era of football which looks more uneven, with the late 1980s and 1990s being more characterised by smaller numbers of dominant stars along with more marginal fringe players. This is consistent with the talent pool likely being shallower in the 1980s or 1990s than today, but also may suggest a more naive approach to tactics which suited the natural stars.

Interestingly, there’s a spike in player value inequality at the point of the most recent expansion. The entry of Gold Coast in 2011 and GWS in 2012 did expand the player base, and in particular it created two new teams filled mostly with teenagers. The early expansion era coincided with inequality in player value returning to levels not seen since the early 2000s. Evidently, having two very weak teams full of low-value, poorly performing players who cycled in and out of the teams, meant that there was a greater disparity in player values across the league.

However, very quickly, this inequality seems to have dissipated, as those sides improved and the league’s talent became better distributed. Rather than a dilution issue, there looks to have been a temporary distribution issue with the masses of young draftees in those teams.

The theoretical “pyramid” and Pareto principle

An important view has been put forth by Bill James, in his Baseball Abstract of 1988 (h/t Beyond The Box Score):

“Talent in baseball is not normally distributed. It is a pyramid. For every player who is 10 percent above the average player, there are probably twenty players who are 10 percent below average.”

This makes the Gini table above seem more logical – the more players you expose to the top leagues, the more even the overall base becomes. But perhaps even a pyramid is misleading, and potentially over-representing the terrible bottom layer.

In that sense, talent is better thought as not a Bell curve distribution but instead a power-law or Pareto distribution, where the elite players stand out as producing peak output, and the rest are more interchangeable. To this degree, research has been conducted with respect to NBA and MLB wins produced (via various advanced metrics) indicating that the talent curve significantly flattens beyond the top few players on each side.

Basically, these theories indicate that the gaps between the best player and the 50th best player is likely greater than the gap between the 100th best and 400th best. Using last year as an example, this holds up to some degree:

| Player | mPAV Rank | Total mPAV | Difference to above rank |

| Dangerfield, Patrick | 1 | 0.857 | |

| Rich, Daniel | 50 | 0.386 | 0.471 |

|

|

|||

| Heeney, Isaac | 100 | 0.229 | |

| Dickson, Tory | 400 | -0.258 | 0.487 |

Using HPN’s mPAV per game player value measure, and ranking each player in the league (minimum five games played), the gap between the best player and the 50th is about the same as between the 100th best player and the 400th.

In short, the curve is flattened. This also implies two other things:

- An AFL league with even substantially less than 18 teams is digging deep into the “long tail” of talent to fill teams, and the difference between, say, 14, 16, 18 and 20 teams would not be significant.

- Roughly the next couple of thousand best players in the country are all not much worse than the 400th best. That’s a big talent pool to fill out the last few hundred spots in team lists, no matter how many teams there are in the AFL. A lot of potential AFL standard players are not playing in the AFL.

Given that there is little perceivable difference between, say, the 500th and 1000th best football players, the only slight issue with peak quality is the redistribution of the super elite – the top 50 to 100 – between each clubs. If you draw the line at 50 truly great players at any one time, that means that teams currently have 2.77 “great” players. In the 16 team era, it would have been 3.125, and if expansion to 20 teams were to take place, it would be roughly 2.5 great players per team.

This difference is marginal at best.

The money

There’s a few other reasons to think that the talent pool of the AFL has grown since the 1980s or 1990s, most of which can be boiled down to this: there’s a hell of a lot more money in footy these days.

To start with, players are paid a lot more, relative to other professions, than they used to be.

In 1996, as laid out in the AFL’s bargaining agreement, the minimum AFL player base salary was $15,000 per year plus $1000 per game. Average Weekly Earnings in Australia for men employed full-time were $721 per week or $37,500 per year. The earnings potential of football was for many aspirants probably actually lower than for many other professions. These days, draftees start out at a base of $80,000 plus $4000 match payments, which is already around full-time male Average Weekly Earnings ($1,812 per week or about $94,200 per year), and the earnings potential quickly lifts from there.

Higher pay should, all things being equal, expand the talent pool because it means football is relatively more attractive than other jobs. Where in previous years, playing football professionally would have been a more difficult and risky choice for people from difficult circumstances or limited means, these days a higher share of the athletically talented population would be enticed to commit and try for a football career rather than a job in the “real world”.

The explosion in AFL player payments has had another effect, which is decisively killing off former competitor state leagues the WAFL and SANFL as alternative employers. Today, the SANFL and WAFL salary caps are below half a million dollars, making those players semi-professional or at least fairly modestly paid. Today, those leagues serve as alternatives for the many unsuccessful AFL aspirants, letting them still ply their trade for a modest income, in conjunction with other activities.

In comparison, in the 1980s and even early 1990s, those two leagues were still a lot closer to the lower pay-scales of the VFL/AFL itself. In the 1980s, and even the early 1990s, we still saw very good players opt not to play in the VFL/AFL as a result. Indeed, both Adelaide and Port Adelaide assembled eventual premiership winning teams mostly via the SANFL in 1990 and 1996. When we talk about the talent pool in the 1980s or any point earlier, we must remember that in this era there was a split talent pool across states, and there were more football clubs, almost 30 of them across the three big footy states, all competing for the best players in the land.

Finally, thanks to the riches of the AFL, talent identification has become professionalised. Early VFL/AFL drafts were very much guesswork, based on little national scouting, often targeting established senior players in other leagues. Today, the business of sifting through every remotely football-adjacent teenage boy in the country to find the best talent involves dozens of full time professionals at the AFL and its 18 clubs. Better scrutiny and development pathways must surely mean the talent pool is being better explored and exploited than in earlier eras.

So why the “dilution” myth?

All this raises the question, why do smart, knowledgable football insiders continue to not only claim there’s a diluted talent pool due to AFL expansion, but assume it as a given?

The easiest theory (and maybe the most correct one) is nostalgia. In almost all creative fields – and let’s include sport as creative for a second – the feats of the past gain in stature for those who lived through them. Remembering when Malcolm Blight kicked a goal from just outside the 45 metre centre square has been replayed over in the minds of many endlessly, while the efforts of (say) Taylor Walker from a similar range well inside the 50 metre square haven’t had the same chance to gain cultural relevance.

The game has certainly changed a lot, and many from the older generations complain about the aesthetics of the game compared to what they knew. That’s understandable, because we all remember our formative years, when we were ourselves at our mental and physical peaks, as the brightest and best era of our lives.

Nostalgia can’t be measured by any of the factors discussed above, and likely won’t be dissuaded by them. But it’s critical to remember that progress doesn’t just occur in the measurable parts of society, but also in the creative and subjective parts.

Another theory based on the above analysis: there’s more talent and more money spent with single-minded focus on winning than ever before, and that makes it harder for the few dominant, naturally gifted stars to roam around doing what they like, in the way that they could in the past, an era mostly characterised by tactically naive 1 vs 1 game plans.

Such critics see players struggling, under pressure levels which would have been unimaginable 30 years ago, to execute kicks and handpasses. They recall an era where more open play meant better-looking skills. They watch highlights of earlier football eras, omitting the bad games and the errors, the bottom table slogs in the mud at Moorabbin, the depths which the Bears and Swans and Fitzroy plumbed.

The deluge of replays of older games in the COVID-19 era has shown that this ability gap is clear – and that it is undeniable that football as currently played is the highest, most talented level of football that has ever been played.

The mistake comes when such critics conclude that a failure to live up to golden eras of memory means that players today are less talented. In fact, it’s probably precisely the opposite – the AFL has changed aesthetically because there’s much more talent out there than ever before, and it’s being harnessed much more ruthlessly, all clashing up against and cancelling out other individual talent.

And of course this means that talent pool availability should not be a cause for argument against recent expansion, nor against possible future expansion.